It had been two years since an alphabet for the Mountain* language had been developed, a project completed with local academic leaders. Two years since the first book in the language had been introduced—a collection of traditional local folktales. Two years since we had been able to visit. We wondered if people would be using the new alphabet and if anyone would be reading the book.

Now, after all this time, we had the opportunity to visit the mountain villages again. As soon as we arrived at our hosts’ home, their eight-year-old daughter greeted us with her copy of the book in hand. Her eyes shone with excitement as she read fluently. The book had been a birthday present and was one of her chief treasures. She was reluctant to share it with her younger brother, lest he damage her special book. But when we gave the little brother his own copy, everyone was happy.

As it turned out, there was no need to advertise the book—when word got out we were there, children from all over the village came to request a copy of their own. We gave some away as gifts and left others in the shops to be sold at an affordable price.

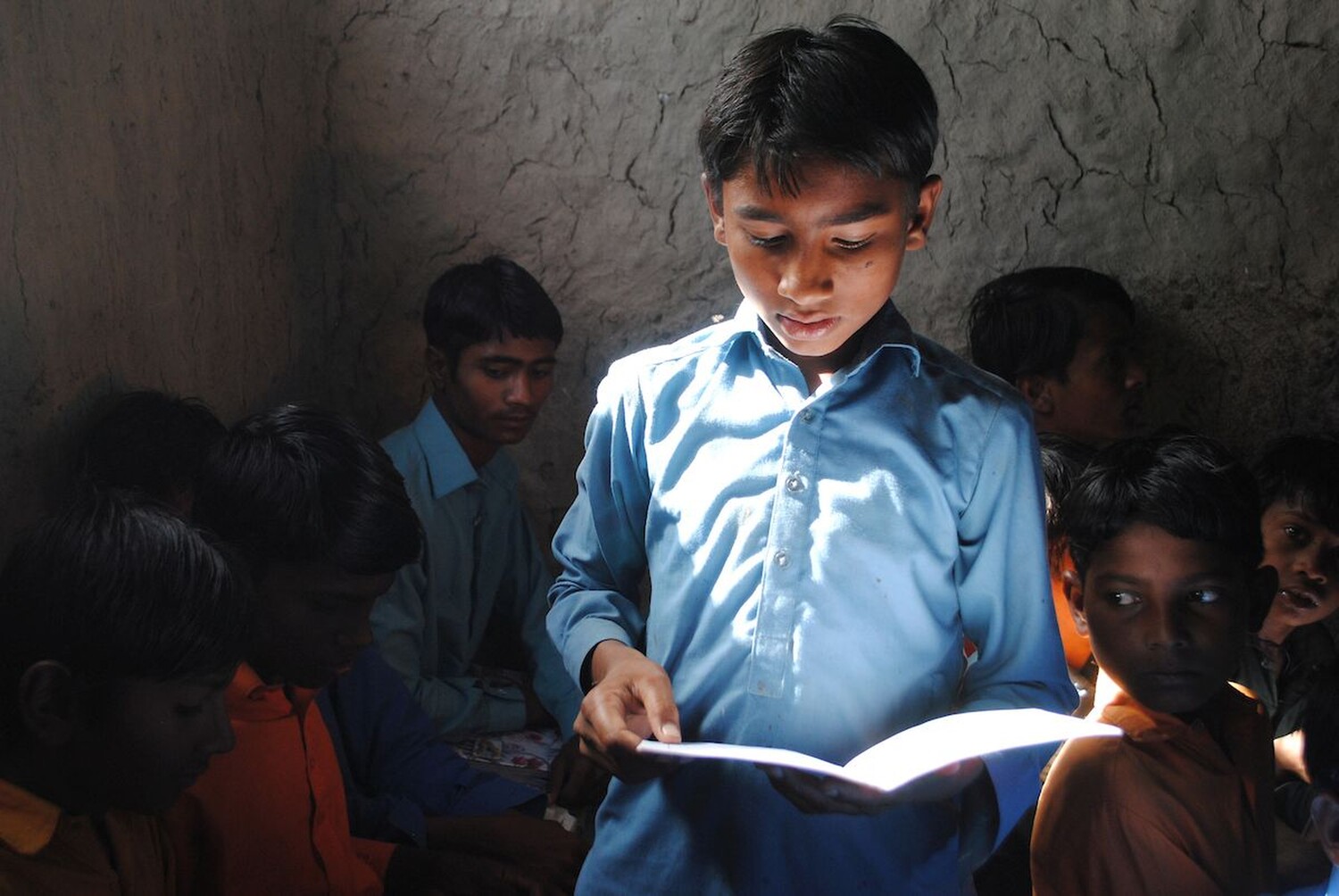

What was even more impressive was that the villagers were trying to write using the new alphabet. I spent many hours sitting on logs sharing my entire stock of pens and paper with children competing among themselves to see who could write the best story. We travelled to other villages in the region in order to collect more stories, legends and folktales. People from the first village introduced us as “those who brought the book,” and sent us to their great-grandfathers—the old storytellers.

We found that the smaller the village, the more legends, myths, and folktales the people could remember. It took a month for us to reach every village in the region. In each village we left some copies of the original book, either as a gift or intended for sale in the local market.

During our trip we collected enough audio recordings for several new books: a collection of local folktales for older children, a book of local poetry and songs connected with the tradition of summer pastures, and a book of local legends and myths related to the religion the people practiced. All these are genres that have been dying out. But now the Mountain community has a renewed desire to preserve these tales.

We are now back in the capital city with the stories of the great-grandfathers. We look forward to a continued close partnership with the Mountain communities in the preparation of the second book in their language.

*Pseudonym. Author's name and locations withheld due to sensitivity.