As a training workshop for First Nations mother-tongue Bible translators was winding down this past April in Guelph, Ont., Zipporah Mamakwa of the Oji-Cree translation team eagerly shared something with her colleagues on other teams.

The soft-spoken teacher from Kingfisher Lake, Ont., said a tribal elder had asked her to come to his house to talk about the Oji-Cree Bible translation project there. The elder said something came to him—a dream—in the middle of the night. He told Zipporah: “I want to encourage the translators to continue on at this Bible translation project, because God is doing something wonderful and powerful in this land.”

When an elder says something like that, it represents the most powerful support you can get, Zipporah told a dozen peers at the workshop.

“And he continues to encourage me to make sure that I pass it on to others,” she added. “So there—I have passed it on: ‘God is doing something powerful and wonderful in this land amongst our people.’ ”

The Oji-Cree elder’s dream-inspired comment may sound grand, but it is no overstatement. After several hundred years of missionary and church ministry among Cree First Nations people, finally there is an increasing local push to see heart-language translations of God’s Word reprinted, completed, or started.

Called the Cree Initiative, this project could impact 100,000-plus people in five related Cree language groups, from Alberta to Ontario. They include: Northern Alberta Cree (spoken in 20-plus communities); Plains Cree (70-plus communities); Woods Cree (20-plus communities); Swampy Cree (20-plus communities) and Oji-Cree (12-plus communities). This cluster of languages—among the largest and most viable in North America—features grammatical structures that are very much alike, with speakers who share similar indigenous cultures.

Indigenous Faith Needs Indigenous Language

While Bible translation efforts in this project may eventually expand to other First Nations languages, the Cree Initiative’s focus for the foreseeable future is on the five Cree languages. Whatever languages are involved, Mark MacDonald, the Anglican Church’s national indigenous bishop, is eager to see it happen.

MacDonald says that Christian faith is quite vibrant in a lot of communities. However, poverty and the inter-generational effects of oppression and forced programs of assimilation (such as the residential schools tragedy), have produced “toxic conditions” in many places.

“These are at the heart of the ministry challenges the gospel faces in First Nation communities today,” says MacDonald.

The way many Aboriginal people look at the Christian Church has been deeply marred by the residential school experience in Canada, he says. “Today, however, many separate the gospel and Jesus from that experience, and look to faith as essential to rebuilding indigenous life and community.”

And, crucial to deepening faith among First Nations are the Scriptures in the mother tongue, stresses MacDonald. “Indigenous theology depends on indigenous language. Revitalization of language and a vital and effective faith depend on each other.

“I believe that ‘the Word made flesh’ requires local languages. The Pentecostal truth that God speaks to us in the mother tongue is a part of the Church’s foundation. Everyone wants to hear the gospel in ‘their language,’ even if that language is being lost.”

MacDonald asserts that every major language among First Nations in Canada should have a mother-tongue translation that meets the community’s stated need.

Locally driven Priorities

MacDonald helped to set the initial goals for the Cree Initiative, when he gathered with First Nation representatives at a mid-June 2014 meeting in Prince Albert, Sask. Staff with Wycliffe Bible Translators, the Canadian Bible Society (CBS) and others were also there.

Myles Leitch, CBS director of Scripture translation, says the goal was to hear what the First Nations leaders in attendance wanted done and for them to identify what help they actually needed.

“It’s not about us wanting to send missionaries in there to do a job no matter what. It’s them saying, ‘We really need to have Scriptures in our language.’ ”

The Cree church leaders requested technical training and assistance from Wycliffe and CBS, including providing mother-tongue translator (MTT) training workshops (see related story, "Dear Diary") and translation consulting.

Wycliffe’s Bill and Norma Jean Jancewicz, who are facilitating the effort, have led two such workshops so far, as well as onsite training for MTTs. The Jancewiczes draw on more than 28 years of experience with the Naskapi people of Quebec, who speak a related language in the Algonquian family of languages that includes Cree (see Word Alive, Spring 2013).

Translators with the Naskapi, who already finished a New Testament and are working on the Old Testament, attend the Cree MTT workshops. The Naskapi representatives both encourage the Cree translators and share insights from their own experience.

Bill hopes for increased Naskapi involvement. “I envision them becoming trainers themselves at some point, but they’re not there yet. They don’t have the confidence or capacity to train at a workshop. But they will. Right now they can share what God is doing in their lives and their project.”

To that end, Silas Nabinicaboo, one of five Naskapi Bible translators, shares some advice for the other First Nations translators, based on his 20 years of experience. “Ask God to give you strength, courage, to do that. If you get stuck with [translating] any words, seek the help of an elder. I like to use elders because they know the language more than I do.”

He says that in the end, Bible translation will be worth all the hard work, because it will be able to deepen Christian faith among the Cree. “It’s important to have God’s Word in their own language—in their heart, in their heads.”

Not Yet or Just Starting

The Jancewiczes hope to help spawn a vision for Bible translation among the Northern Alberta Cree and Swampy Cree at some point. However, there are still no local Bible translation project committees or trained mother-tongue translators in place, which are crucial to championing and doing the work in those languages.

“So we pray a lot,” says Norma Jean. “’Lord, if you open that door, then we’re going to step through it.’ ”

In Woods Cree, work is in the very early stages. A key player in future Bible translation will surely be Rev. Sam Halkett of the Anglican Church, who ministers in Cree communities near Prince Albert, Sask.

An avid teacher of his language for years, Halkett is responsible for three church services each Sunday. English Scriptures, says Halkett, provide many Woods Cree speakers with only a surface understanding of Christian truth.

“I think they’re missing the real heart of the gospel itself, in the language of our people,” he says. “The power of the Word in our language changes our thought patterns, and it is more meaningful and relevant to who we are as aboriginals. And God is the Word, God is the Spirit, and He is in our language—it is a gift to us.”

He hopes to assemble a team of translators to bring God’s Word to his people in their heart language.

Most Recent Translation

Oji-Cree is the latest language to see translation begin. The visionary behind the effort is Lydia Mamakwa, area bishop for the Anglican Church’s Indigenous Spiritual Ministry of Mishamikoweesh, the first completely indigenous diocese. She leads a team of six mother-tongue translators at Kingfisher Lake, Ont. Mamakwa and a colleague had personal experience in residential schools where their mother tongue was prohibited (see story, "I Almost Lost My Language").

Since 2015, with a strong community translation committee behind them, the team has translated 2,000-plus verses into Oji-Cree for their church’s Bible readings each Sunday. This is a welcome change from using Scriptures translated for other types of Cree, which the Oji-Cree don’t fully understand.

“People are very happy with it,” says Mamakwa. “People say it makes it so much clearer to understand the message and what God is saying. It becomes so real.”

Her Bible-translating sister, Zipporah, says Oji-Cree Scriptures will play a key role in the crucial work of maintaining the language.

“It is my belief as a language teacher that the language amongst our children brings a sense of identity, a sense of belonging, a sense of security and comfort.

“Without our language we are lost, our children are confused,” adds Zipporah. “We don’t feel whole without our language.”

Plains Cree on the Way

The Plains Cree portion of the Cree Initiative received a boost by being named a priority at the Prince Albert meeting. Since the early 1970s, CBS, Wycliffe and First Nations church leaders have been involved in Bible translation efforts for this largest of Cree languages in Canada.

In the 1980s, Cree speaker and Anglican Church minister, Stan Cuthand, started work on a contemporary Plains Cree translation. He completed a first draft of the New Testament and about half of the Old Testament. Many workshops have been held to involve additional Cree speakers in the process of reviewing and giving input to improve the translation.

This review process is now the focus of Dolores Sand and Gayle Weenie (who live in or near Saskatoon, Sask.) with ongoing input at consultations with groups of Cree speakers. Ruth Heeg of CBS has served as co-ordinator and translation consultant, but because of her retirement, other CBS translation personnel will be filling these roles as required.

Both retired teachers, Sand and Weenie are painstakingly checking Cuthand’s draft translation for spelling and grammar, as well as for accuracy and clarity. These two Catholic lay leaders, who grew up in Cree communities in Saskatchewan, are passionate about giving fellow Plains Cree speakers the Word of God.

“In our communities,” says Sand, “there is an emptiness . . . our children need to find the Creator to fill that emptiness. I think that is the strength of this Bible translation work. It’s a way to pass on our faith to future generations—that’s our legacy.”

Weenie says working on the translation is also a way to reverse the impact of residential schools, which prohibited her own parents from speaking Plains Cree as children, in an attempt to break personal links to their culture. “I think about that often and I say, ‘I’m getting the last laugh because I still know the language and I’m trying to pass it on.’

“And for me personally, the Bible is the way of getting a deeper understanding of God.”

As the translation checking progresses and Scriptures are distributed, the two colleagues hope to see God’s Word in Plains Cree used in church lectionary readings.

Heeg says that people respond best to the gospel in their mother tongue. “The indigenous languages are still the mother tongue for a large number of people [in Canada],” she stresses.

Legacy Bible Gets Refreshed

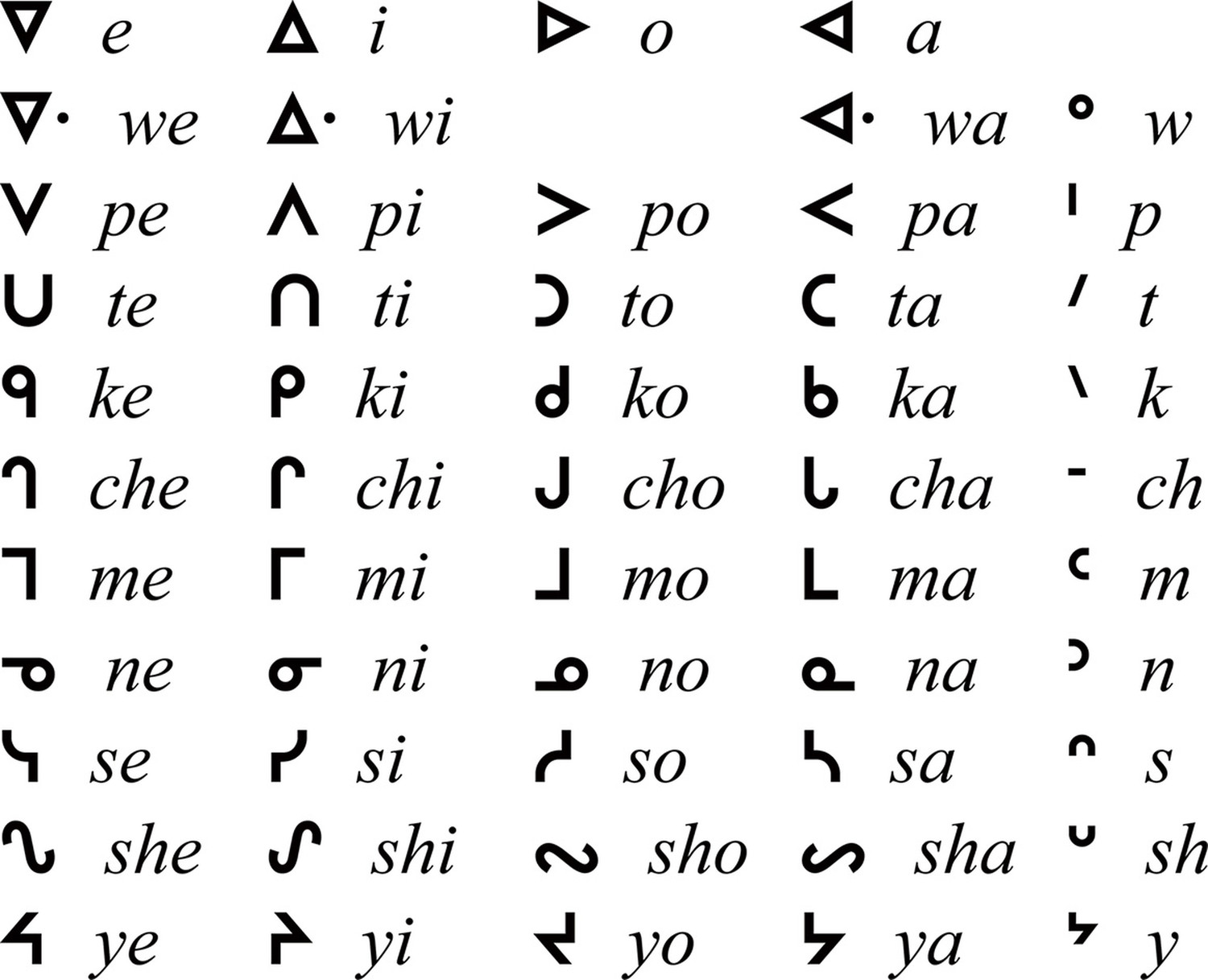

Sand, assisted by CBS’s Heeg, is also helping to check CBS-keyboarded syllabics text of the Scriptures from the out-of-print Mason Cree Bible from the 1860s.

Bill Jancewicz describes this legacy Bible as a Cree equivalent of the English King James version, because it is highly regarded and honoured. As a result, it is found in many churches of First Nations communities no matter the variety of Cree spoken there. “It’s an ‘Indian’ Bible,” he says.

It was translated in 1862 for speakers of a now-archaic Cree “on the plain” of Canada, by Rev. William Mason and his part-Cree wife Sophia, at Norway House, Man. In 1908, the translation was reprinted after a revision by Rev. John Alexander Mackay.

The Mason Cree Bible has been read in First Nations services by generations of catechists, deacons, lay-readers and clergy, who then explained it in the local Cree language. However, younger speakers of these Aboriginal languages have grown up not understanding the older language or the syllabic writing system, so it can’t meet the needs of all Cree speakers.

Nonetheless, because of the Mason Cree Bible’s stature, it is a priority of the Cree First Nations for CBS to reprint it. These Scriptures will also be a searchable, digital reference for current First Nations translators.

Chance for Reparations

Whatever Bible translation work they are part of, the MTTs involved are thankful for the prayers and financial donations of Canadian Christians, including those coming through Wycliffe Canada.

Until Zipporah Mamakwa discovered how the work was funded, she didn’t realize that the broader Canadian Church cared about First Nations believers and their communities. “I would say that the help and support that we get from them is way beyond what we can express our thanks for.”

Bishop MacDonald says non-Aboriginal Christian support for the Cree translation work acts as one way to make amends for the past mistreatment First Nations people have experienced.

“This is a chance for reparations that will lead to revitalization that will bless and enhance the whole Church in Canada.”

•••••